A question recently came up at work about benchmarks between Java and Scala. Maybe you came across my blog post because you too are wanting to know which is faster, Java or Scala. Well I'm sorry to say this, but if that is you, you are asking the wrong question. In this post, I will show you that Scala is faster than Java. After that, I will show you why the question was the wrong question and why my results should be ignored. Then I will explain what question you should have asked.

The benchmark

Today we are going to choose a very simple algorithm to benchmark, the quick sort algorithm. I will provide implementations both in Scala and Java. Then with each I will sort a list of 100000 elements 100 times, and see how long each implementations takes to sort it. So let's start off with Java:

public static void quickSort(int[] array, int left, int right) {

if (right <= left) {

return;

}

int pivot = array[right];

int p = left;

int i = left;

while (i < right) {

if (array[i] < pivot) {

if (p != i) {

int tmp = array[p];

array[p] = array[i];

array[i] = tmp;

}

p += 1;

}

i += 1;

}

array[right] = array[p];

array[p] = pivot;

quickSort(array, left, p - 1);

quickSort(array, p + 1, right);

}

Timing this, sorting a list of 100000 elements 100 times on my 2012 MacBook Pro with Retina Display, it takes 852ms. Now the Scala implementation:

def sortArray(array: Array[Int], left: Int, right: Int) {

if (right <= left) {

return

}

val pivot = array(right)

var p = left

var i = left

while (i < right) {

if (array(i) < pivot) {

if (p != i) {

val tmp = array(p)

array(p) = array(i)

array(i) = tmp

}

p += 1

}

i += 1

}

array(right) = array(p)

array(p) = pivot

sortArray(array, left, p - 1)

sortArray(array, p + 1, right)

}

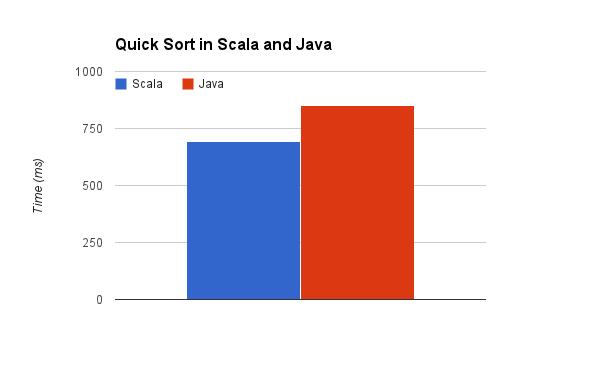

It looks very similar to the Java implementation, slightly different syntax, but in general, the same. And the time for the same benchmark? 695ms. No benchmark is complete without a graph, so let's see what that looks like visually:

So there you have it. Scala is about 20% faster than Java. QED and all that.

The wrong question

However this is not the full story. No micro benchmark ever is. So let's start off with answering the question of why Scala is faster than Java in this case. Now Scala and Java both run on the JVM. Their source code both compiles to bytecode, and from the JVMs perspective, it doesn't know if one is Scala or one is Java, it's just all bytecode to the JVM. If we look at the bytecode of the compiled Scala and Java code above, we'll notice one key thing, in the Java code, there are two recursive invocations of the quickSort routine, while in Scala, there is only one. Why is this? The Scala compiler supports an optimisation called tail call recursion, where if the last statement in a method is a recursive call, it can get rid of that call and replace it with an iterative solution. So that's why the Scala code is so much quicker than the Java code, it's this tail call recursion optimisation. You can turn this optimisation off when compiling Scala code, when I do that it now takes 827ms, still a little bit faster but not much. I don't know why Scala is still faster without tail call recursion.

This brings me to my next point, apart from a couple of extra niche optimisations like this, Scala and Java both compile to bytecode, and hence have near identical performance characteristics for comparable code. In fact, when writing Scala code, you tend to use a lot of exactly the same libraries between Java and Scala, because to the JVM it's all just bytecode. This is why benchmarking Scala against Java is the wrong question.

But this still isn't the full picture. My implementation of quick sort in Scala was not what we'd call idiomatic Scala code. It's implemented in an imperative fashion, very performance focussed - which it should be, being code that is used for a performance benchmark. But it's not written in a style that a Scala developer would write day to day. Here is an implementation of quick sort that is in that idiomatic Scala style:

def sortList(list: List[Int]): List[Int] = list match {

case Nil => Nil

case head :: tail => sortList(tail.filter(_ < head)) ::: head :: sortList(tail.filter(_ >= head))

}

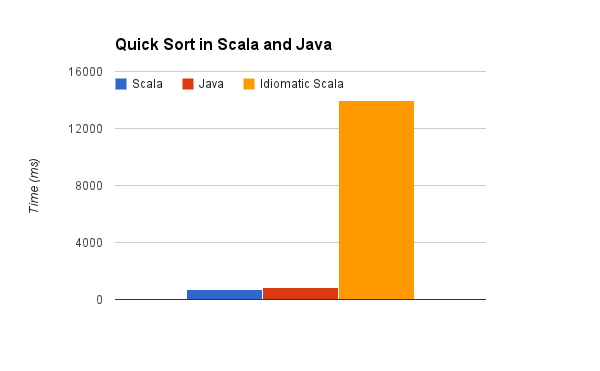

If you're not familiar with Scala, this code may seem overwhelming at first, but trust me, after a few weeks of learning the language, you would be completely comfortable reading this, and would find it far clearer and easier to maintain than the previous solution. So how does this code perform? Well the answer is terribly, it takes 13951ms, 20 times longer than the other Scala code. Obligatory chart:

So am I saying that when you write Scala in the "normal" way, your codes performance will always be terrible? Well, that's not quite how Scala developers write code all the time, they aren't dumb, they know the performance consequences of their code.

The key thing to remember is that most problems that developers solve are not quick sort, they are not computation heavy problems. A typical web application for example is concerned with moving data around, not doing complex algorithms. The amount of computation that a piece of Java code that a web developer might write to process a web request might take 1 microsecond out of the entire request to run - that is, one millionth of a second. If the equivalent Scala code takes 20 microseconds, that's still only one fifty thousandth of a second. The whole request might take 20 milliseconds to process, including going to the database a few times. Using idiomatic Scala code would therefore increase the response time by 0.1%, which is practically nothing.

So, Scala developers, when they write code, will write it in the idiomatic way. As you can see above, the idiomatic way is clear and concise. It's easy to maintain, much easier than Java. However, when they come across a problem that they know is computationally expensive, they will revert to writing in a style that is more like Java. This way, they have the best of both worlds, with the easy to maintain idiomatic Scala code for the most of their code base, and the well performaning Java like code where the performance matters.

The right question

So what question should you be asking, when comparing Scala to Java in the area of performance? The answer is in Scala's name. Scala was built to be a "Scalable language". As we've already seen, this scalability does not come in micro benchmarks. So where does it come? This is going to be the topic of a future blog post I write, where I will show some closer to real world benchmarks of a Scala web application versus a Java web application, but to give you an idea, the answer comes in how the Scala syntax and libraries provided by the Scala ecosystem is aptly suited for the paradigms of programming that are required to write scalable fault tolerant systems. The exact equivalent bytecode could be implemented in Java, but it would be a monstrous nightmare of impossible to follow anonymous inner classes, with a constant fear of accidentally mutating the wrong shared state, and a good dose of race conditions and memory visibility issues.

To put it more concisely, the question you should be asking is "How will Scala help me when my servers are falling over from unanticipated load?" This is a real world question that I'm sure any IT professional with any sort of real world experience would love an answer to. Stay tuned for my next blog post.

Hi! My name is James Roper, and I am a software developer with a particular interest in open source

development and trying new things. I program in Scala, Java, Go, PHP, Python and Javascript, and I work

for

Hi! My name is James Roper, and I am a software developer with a particular interest in open source

development and trying new things. I program in Scala, Java, Go, PHP, Python and Javascript, and I work

for